Samuel Insull: The Father of Light Pt. II

Natural Monopoly

Click here to read Part I of this series.

Chicago wasn’t enough for Insull. With his wingspan too broad and his ambition too large, he began to pressure his entire industry to adopt his perspective on the nature of the utility business. Monopoly wasn’t just right for him; it was right for all of them. If they did as he said, they could grow their territories beyond neighborhoods and cities.

To the members of the National Electric Light Association (the major trade group at the time), Insull argued that utilities were “natural monopolies,” meaning the “best service at the lowest possible price can only be obtained […] by exclusive control of a given territory being placed in the hands of one undertaking.” Didn’t his success in Chicago prove it? He’d gotten rid of all that competition (and the waste and redundancy that came with it) and delivered low rates to even more people. Moreover, monopoly status would make it easier for them to get money from investors, who kept a tight grip on their money whenever they surveyed the chaotic, competitive world of electric power. It was a new industry; new meant risky; risky meant high borrowing costs for utilities.

Yet there was a curious twist in his argument: in order for “natural monopolies” to exist, the government had to formally recognize them as such and enshrine their status in law, which meant welcoming regulation with open arms. Insull’s vision of such a law would involve “a single operator be[ing] granted an exclusive franchise to provide electricity prices fixed by state commissions based on ‘cost plus reasonable profit.’” Competition would cease, customers would see their bills drop, and utility stocks and bonds would become enticing, unleashing a torrent of cheaper capital from banks. In exchange, utilities would bow to state-level regulatory commissions. At first, his peers scoffed. Welcoming regulation not only looked like bad business; it sounded downright un-American.

The current of the times flowed in Insull’s direction, however. At the turn of the century, a new political camp had emerged. The Progressive movement, under the imprimatur of which the contemporary activist still flies, stepped onto the scene. This band of elitist technocrats brought with them new and controversial assumptions about the nature of American politics. They lionized Abraham Lincoln, not as the Great Emancipator and defender of America’s founding principles, but as the founder of a centralized (white) nation-state. The Union Army’s victory, which relied on an increasingly centralized federal government, had disproven the Founding Fathers’ belief in the efficacy of limited government. Through scientific management and bureaucracy, a rational state could be born, one more able to handle the novel challenges of industrialization and urbanization. A combination of German philosophy, Social Darwinism, and faith in science welded together to form their worldview.

Progressives held many conflicting commitments. They supported such putatively egalitarian measures as income taxes, welfare, women’s suffrage, and the direct election of senators. At the same time, they harbored an hierarchical worldview marked with virulently racist ideas about eugenics. This anti-democratic streak also manifested in an almost religious faith in top-down scientific management and support for the prohibition of alcohol. On the whole, Progressives saw themselves as elite shepherds tasked with herding society through the harsh wilderness of laissez-faire capitalism and into the Edenic pasture of expert management and rational planning. Confronted with the new corporate behemoths of the industrial era, Progressives hoped the state could serve as a bulwark against the new rising challenge of unbridled corporate power that harvested private gain for the public good through government intervention.

“The aggrandizement of corporate and individual wealth,” wrote Progressive intellectual and co-founder of The New Republic, Herbert Croly, required “the regulation of commerce, the organization of labor, and the increasing control over property in the public interest” preferably by the government. Everyday people were not up to this task because the “average American individual” was “morally and intellectually inadequate to a serious and consistent conception of his responsibilities as a democrat.”

Progressive commitments to eliminating inefficiencies, “rationalizing” politics, and bolstering the government’s strength fit well with Insull’s vision of utilities as a natural, regulated monopoly. Especially because reducing the “waste” of competition complemented Progressives’ porto-environmentalist concerns about conserving natural resources. Insull worked with Progressive stalwart and future Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis to publish a three-volume report on the utility industry and its regulatory framework. This 1907 report, largely funded by the utility industry, vindicated Insull’s regulated monopoly vision. Within months of its publication, it had inspired legislation that became law in Wisconsin and New York, establishing regulators in both states. Twenty-five other states followed suit, establishing their own utility commissions.

Once regulated, utilities were obligated to serve all within their fiefs without discrimination. This meant a tidal wave of new customers for kilowatts. To supply their demand, utilities could now avail themselves of the cheap capital needed to build newer, bigger power plants at “just and reasonable” rates that covered both operating costs and a return on their invested capital. Eminent domain and the legal eradication of competition were their rewards. Provided a utility could justify its asset purchases, it could recoup costs and turn a profit on them. In short, utilities got paid more to spend more.

But what did “just and reasonable” mean in practice? Who decided what constituted a fair return on fair value? The regulators who helmed the state power commissions, ostensibly. But discharging their regulatory duty proved no mean feat—discerning the “proper” rates often fell beyond the grasp of many state regulators because utility investments were so novel and complex. Two related problems arose: utilities’ well-heeled, savvy lawyers could undermine any state commission’s claims regarding the “unjustness” or “unfairness” of utilities' investments or rates; and, as utilities grew by expanding their territories beyond state borders, they escaped any one state’s full regulation. Regulatory capture and evasion became standard features of the new regime.

Regardless, state regulation did deliver the promised economies of scale, birthing a political-regulatory framework that would endure for nearly a century. Men like Insull claimed their crowns as they watched their monopoly kingdoms expand and their generation grow while competition faded. Eventually, nearly every single state had its own utility commission. After state-regulated monopolies became the norm, the industry consolidated rapidly: the number of privately owned utilities dropped by half, while the average generation owned by the surviving utilities nearly sextupled. The entire industry now reflected Insull’s vision.

No doubt, Insull’s star was rising, though his profile remained confined to the Midwestern region in which he headquartered his business. The outbreak of the Great War, however, would change all of that, vaulting him onto the national stage. Thanks to wartime production and wartime shortages, Insull would snatch up industrial customers impossible to sell power to before, exploding consumption of his product. And it was through his participation in the war effort that he learned the advertising and public relations skills that would help him cement his empire—and then raze it to rubble.

A fraught suture-work of alliances held Europe together in its imperial era. The logic of the continent’s international relations sought détente through these alliances: all knew a conflict between any of the major powers could foment into a global conflagration, the potential for which served as its own deterrent. Yet the imperial era had also inspired widespread nationalist movements within smaller countries that sought to regain their sovereignty and to retain their ethnic identities which the homogenizing pressure of empire now threatened. These nationalist movements hazarded the tense peace Europe had delicately maintained, then shattered it.

In June of 1914, a young member of a Serbian ultranationalist group assassinated the presumptive heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie, the Duchess of Hohenberg. A diplomatic crisis spilled over into the next month and eventually crested into war. As their western brethren fixed their bayonets, many Americans looked on in horror and aversion—why should they join Europe’s fight? Despite initial reluctance, the magnetic pull of Western conflict drew hundreds of thousands of American troops across the Atlantic and into the trenches.

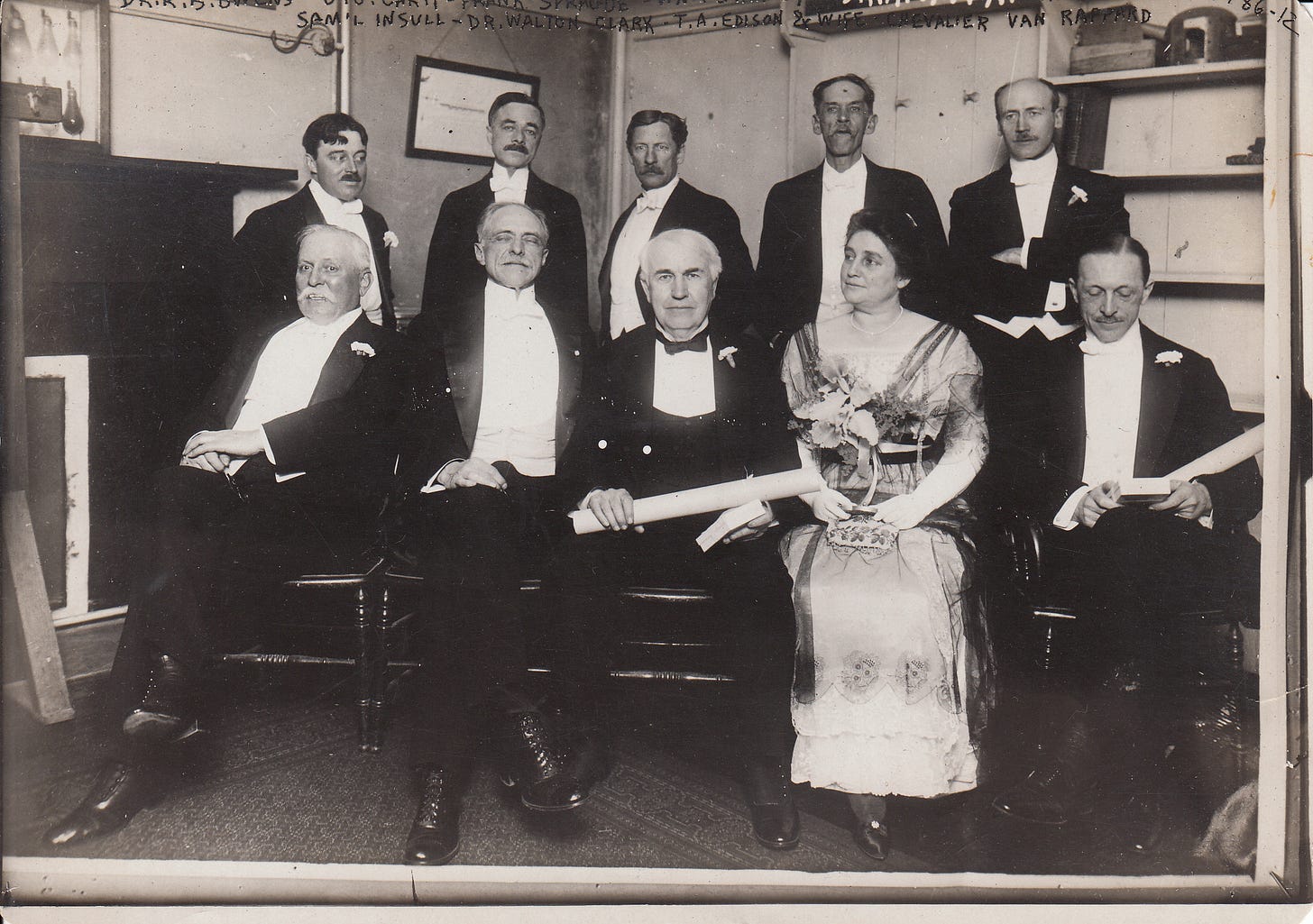

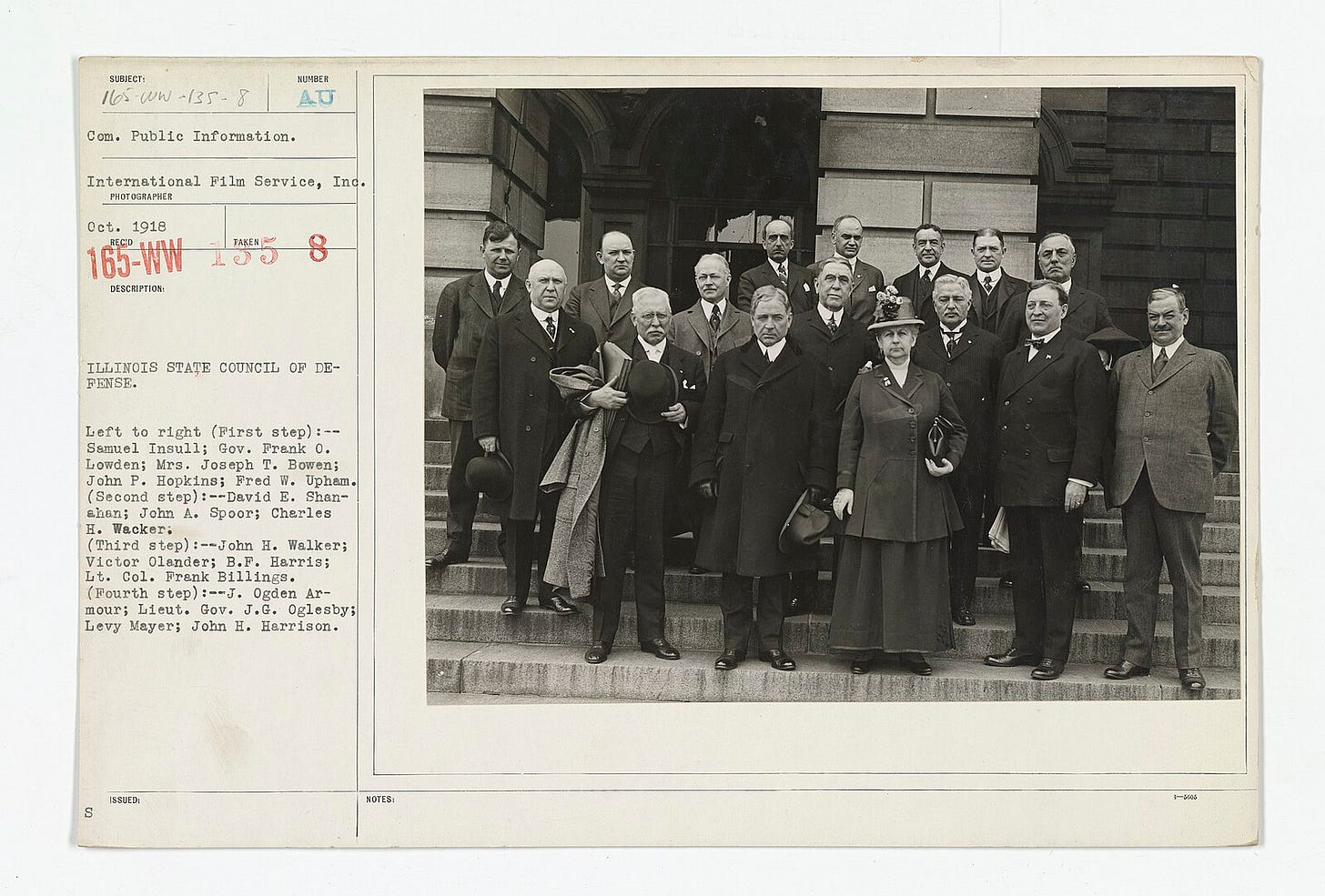

Insull’s reputation positioned him to assume greater civic leadership when American entered the war in 1917. Upon America’s declaration of war, Illinois Governor Frank Lowden asked Insull to chair the state’s Council of Defense. President Woodrow Wilson envisioned each state forming a National Council of Defense dedicated to spying on German-Americans. Insull assumed the role in Illinois, but had no interest in violating the civil liberties of a large portion of his customer base. Since the mid-19th century, Chicago, and the Midwest more generally, had been a bastion of German immigrants. Instead of targeting Germans in particular, Insell gathered together business and civic leaders to propagandize the war through public relations and the sale of Liberty bonds. His boosterism proved successful. Insull whipped up a bloodthirsty furor for war by creating one of the most organized, ruthless, and precise PR campaigns Americans had ever witnessed.

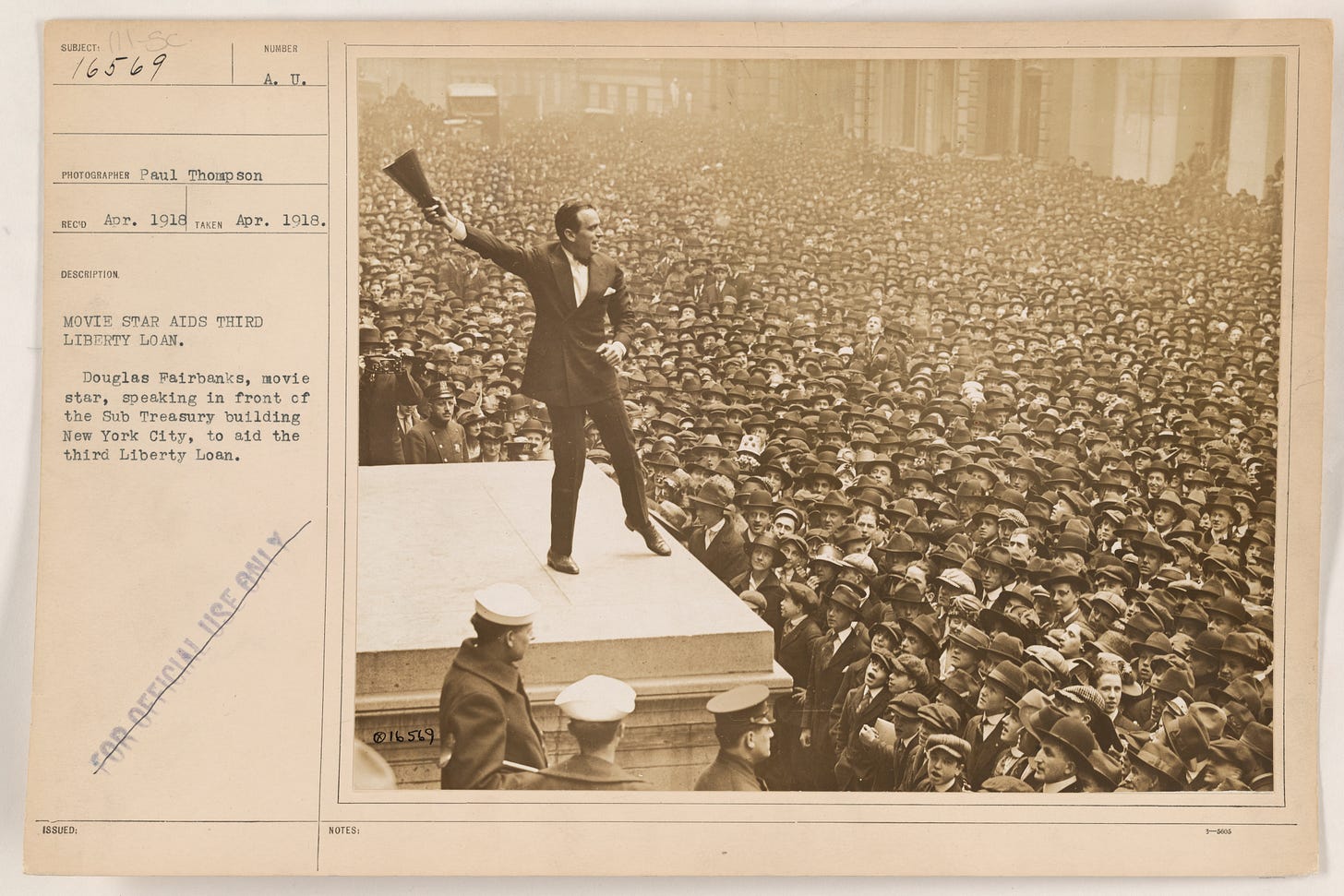

By the end of 1917, Insull had instantiated an hourly schedule of pro-war public gatherings in churches, public buildings, schools, and households in every single community across the state of Illinois to encourage the “appreciation of the ideals of true patriotism and love of country” and “proper war spirit.” His efforts even birthed a national agency called the “Four-Minute Men,” who turned out a slate of speakers to preach a four-minute pro-war gospel to theater audiences. This experiment soon gained national uptake once Insull’s compatriots learned of its success in Chicago, where Insull’s 2,000 speakers addressed 700,000 people a week. By war’s end, the national ranks of the Four-Minute Men had swelled to 75,000. Insull became America’s propagandist-in-chief.

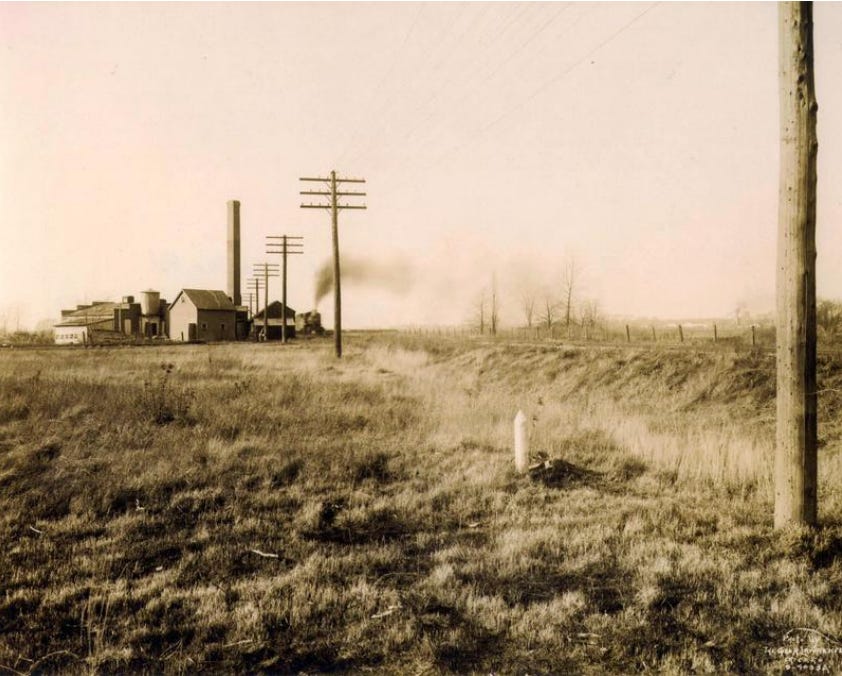

On the material side, the tumult of war delivered to Insull a prize he had coveted for decades: factories. Heavy industry was a power-hungry business, a coal-hungry business. But factories jealously guarded their private power plants, not just because the plants were affordable, but because owning a private plant conferred greater control. Why surrender to an outside force that could affect the bottom line with unfavorable electricity rates, especially when coal was so cheap? But if the price of coal climbed to a steep enough peak, then heavy industry’s private power plants would be rendered uneconomical, since they were small and less efficient than those of the utility industry. Again, electricity was a game of scale.

During WWI, American manufacturing took off as US exports to Europe tripled. With the breakneck pace of production, coal prices tripled. The increasing price of coal made economies of scale undeniable. By 1918, Commonwealth Edison’s power plants could crank out a kilowatt-hour per every 2.5 pounds of coal, while the small private plants housed in factories needed about 9 pounds of coal to produce the same. In the face of skyrocketing demand and the tightness of supply, engineers, the press, and ultimately the American government adopted Insull’s view: factories had to forego their private plants and buy electricity from utilities. To pressure factories to make the switch, the federal government intervened in the market and prioritized allocating coal to utilities, delivering industrial customers directly into the hands of Insull.

The war ended in 1918, with Insull as one of its major victors. After the armistice, the Army, engineers, and industry insiders ratified the new consensus: electricity was best procured from vast, interconnected utilities. Insull explained to San Franciscans in 1918 that the “lightless nights” and “heatless days” of the war years had taught Americans that vertically integrated monopolies were an economic necessity. Insull was now the national face of the most revolutionary industry Americans had witnessed since the railroad.

Cultural and political shifts also moved in Insull’s favor as America put the war years behind them and entered the Roaring Twenties. Progressives, Insull’s allies in the push for regulation, received a huge blow to their credibility and the cause of government intervention, which many associated with the war effort. Then, the Soviet Revolution sparked a Red Scare in 1919, which provoked a wave of hostility to bureaucracy of all kinds, at the same time that post-war disillusionment was turning some reformers away from their old cause. The call for limited government grew louder, as did a personal animus toward the federal government when Prohibition, an elite project pursued by a small band of moral crusaders, served as many citizens’ first individual engagement with federal power. Prohibition caused a ripple effect that sharpened Americans’ suspicion of the government’s intentions. Better to distrust government, Americans reasoned, and place faith back in private hands.

Capitalizing on this swing in their favor, private enterprise boosted its public approval through an emphasis on “service.” Americans began to see these industries as benevolent providers of wealth. As President Calvin Coolidge put it, “The man who builds a factory builds a temple. The man who works there, worships there.” The people were inclined to agree. The country roared into the prosperity of the 1920s—a glamorous decade of jazz, flapper dresses, champagne, and stock market fever.

Insull’s war-won mastery of PR and advertising, his newly minted national profile, a booming market, and an ascendent public trust in private industry blew powerful gales that would send him sailing into terra incognita. He was sixty-three by war’s end and he still had new domains to conquer.

Thanks for the history lesson, hopefully you will continue to the present.

Minor typo for the next revision: "Especially because reducing the “waste” of competition complimented Progressives’ porto-environmentalist concerns about conserving natural resources. "

complemented

Excellent article.